At a recent conference, a speaker noted as a forgone conclusion that Chabad was the only force shaping the last decade of American Jewry. Prof Adam Ferziger responded strongly and loaded with data that the Yeshivish world has had a great influence in shaping the current American reality. His latest work Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism, examines this claim and in addition offers several other essays where he investigates the changes in American Orthodoxy of the last two decades.

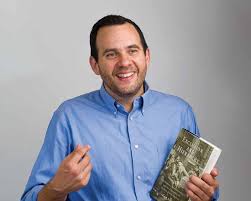

Adam S. Ferziger is a professor and holds the S.R. Hirsch Chair for Research of the Torah and Derekh Erez Movement in the Israel and Golda Koschitsky Department of Jewish History and Contemporary Jewry at Bar-Ilan University. His first book was Exclusion and Hierarchy: Orthodoxy, Nonobservance, and the Emergence of Modern Jewish Identity Ferziger is primarily a social historian looking at community structure, theology plays an ancillary role. Prof Jonathan Sarna praises him, that he “is one of the smartest and most perceptive scholars of Orthodox Jewish life.” I will add that he is also a nice guy.

In his prior work, Exclusion and Hierarchy (excerpt here.) , Ferziger shows how 19th century German Orthodoxy evolved two different approaches toward the non-Orthodox majority. In the initial approach, that became associated with Ultra-Orthodox, the non-Orthodox Jews were simply excluded from the purview of the minority community. In the predominant approach, which emerged in the context of Neo-Orthodoxy, Orthodoxy created space for the nonobservant but spawned a hierarchical culture in which some were seen as keeping the tradition better than others, and as such more “authentic” Jews than others. Hence only the top of the hierarchy could have public religious roles.

In his latest work, Beyond Sectarianism: The Realignment of American Orthodox Judaism, Ferziger arrives at the binary conclusion that American Haredi movements such as community kollels have been socially outgoing, pragmatically protean, and concerned with outreach. In contrast, Modern Orthodoxy – once the pioneering Orthodox movement that engages the spectrum of American – has gravitated toward an inward looking, boundary drawing religious style , and is focused more on raising its own education level. In short, the former has recast itself as outward and outreach oriented, while the later has become more centripetal focused on its own narrow enclaves.

The first part of the book is a collection of Ferziger’s articles on a wide range of topics in American Orthodoxy: Rabbi Yekutiel Yehuda Grunwald , the Lookstein dynasty, and the SSSJ- Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry.

The second part of the book is a theme and variations on the current approaches to sectarianism of American Orthodoxy. In 1965, Charles S. Liebman published a study dividing Orthodoxy into two groups, modern Orthodoxy and Ultra-Orthodoxy. Liebman based this division on the sociological distinction between a “church” group that seeks to be open and broad, as opposed to a “sectarian” group that is only concerned for its own members. Ferziger traces a narrowing of the gap between the two Orthodox trends and ultimately a realignment of American Orthodox Judaism.

Ferziger shows that significant elements within Haredi Orthodoxy have abandoned certain strict and seemingly uncontested norms. He shows how Yeshivish Haredi Jews in the United States are outward looking, non-sectarian, college educated and acculturated in American life. Much of the discussion focuses on the emergence of outreach to nonobservant Jews as a central priority for Haredi Orthodoxy pushing even its core population to new attitudes.

In his focus on Centrism, Ferziger has a long essay, first published a few years ago, on Rabbi Hershel Schachter’s creation of a social boundary by labeling feminism as heresy. Centrism uses this heresy boundary to police its own sect by hunting down violators. He also shows how Rabbi Schachter created an entire historical vision and criteria for authority based on his own newly minted ideas of mesorah. (I am surprised that Ferziger’s article was not cited during last year’s culture wars around women and tefillin. If anyone has antecedent sources, excluding Rav Soloveitchik, for a genealogy of mesorah please email them to me. )

American modern Orthodoxy does not have the same views as 1965 when Charles Liebman predicted that the future of the movement was in the ideas of Rabbi Yitz Greenberg, but that does not make Centrism into a form of Haredi Judaism. Yet, I wonder about the other direction, in that, current practice for many parts of the professional Yeshivish world are more educated and acculturated than some prior forms of modern non-Haredi Orthodoxy.

I have a few mild comments on the work. First, Ferziger replaces Liebman’s terms Ultra-Orthodox with the current word Haredi, to include Yiddish speaking Hungarian Hasidim, Chabad, and American Yeshivish. He is quite aware of the distinctions, but we may need to work on a differentiated nomenclature.

Second, the book has a before and after set up of Liebman in 1965 and then bases his conclusions on 1996-2015. The book and the answers below have a wide chasm between the years of 1975-1995 that needs to be filled in. To judge the change, we need to hear more about Rabbi Norman Lamm, Abraham Twerski, Chait, and JD Bleich, more about NCSY, Ohr Sameach, Touro, the Nefesh organization, and Rebbitzen Jungreis, and an integration of what we know about Artscroll and Daf Yomi.

Third, it was not his task, and it does not take awy from his fine book, but I would like an anthropologist to look at some of the same topics and ask questions about books on the shelf, seforim purchases, family leisure time, household décor, political rally’s, sports, and Americanization. In the 19th century topic of Ferziger’s first book, we already knew to only look for the piano and set of Goethe& Schiller in the family salon of those advocating hierarchy and not exclusion. The book (and interview) touches on economics but I would also like to hear about class, caste, and habitas.

- What is the most important message of your book?

A realignment has taken place within American Orthodoxy, most forcefully in the last two decades, offering an alternative to the previously accepted dichotomy of Modern Orthodoxy and Haredi Orthodoxy. One side of this transition, the “shift to the right” of the Modern Orthodox, has received a considerable attention from prominent researchers in recent decades.

My work supports and offers fresh nuances to this appraisal, but it stands out in highlighting the ways that significant elements within Haredi Orthodoxy have simultaneously abandoned certain strict and seemingly uncontested sectarian norms. In so doing, they have become less monolithic and adopted manners of conduct and attitudes formerly associated with the Modern Orthodox.

Once considered a dwindling relic of European Jewry, American Orthodox Judaism has established itself both as a vibrant American religious movement and as a vital subject of academic interest. Fifty years after the pioneering studies appeared, however, some of the initial definitions and observations need to be reexamined. My book challenges the fixed typological distinctions between Modern Orthodoxy and Haredi Orthodoxy that have held sway from the 1960s in academic and lay discourse. Both sides, then, have contributed toward a narrowing of the former gap between them, engendering a more fluid and complex religious stream.

2) Can you contrast the paths of Modern Orthodoxy and Haredi in the last generation?

Among the generation of American Orthodox rabbis that emerged in the early to mid- twentieth century, there was a strong feeling that Orthodoxy had to try to appeal to as many Jews as possible. At a time when few congregations existed that could boast of a critical mass of fully observant individuals, it was obvious that Orthodoxy would become obsolete if it only catered to the pious. This “broad constituency” approach evolved into part of the ethos of American Modern Orthodoxy’s flagship rabbinical training ground, RIETS of YU.

Modern Orthodoxy’s Americanized, college-educated graduates were dispatched to communities throughout the country with the goal of creating Orthodox congregations that would offer religious services to the entire Jewish population. With this attitude in mind, some even walked a denominational tightrope by accepting pulpits in synagogues with mixed seating. RIETS’ historically groundbreaking role in Jewish outreach was orchestrated during the mid-twentieth century through its Max Stern Division of Communal Services (MSDCS).

In contrast, the Haredi world was created by survivors and remnants of the leadership of the Lithuanian yeshivas and Hasidic dynasties who arrived around World War II and directed their efforts toward recreating the institutions and lifestyles that had been destroyed. Fearful of the seductive power of the treife medina (unkosher state)—which to their minds had tainted the established Modern Orthodox—they set up enclaves in which they could regain their former strength and vitality. As such, their yeshivas and kollels concentrated on producing Torah scholars rather than multitalented pulpit rabbis. If some of their graduates later served in more heterogeneous Orthodox congregations, this was certainly not the primary goal of their mother institutions. The main objective, rather, was to create a community devoted to Torah learning and or/Hasidic teachings a cadre of rabbis and teachers who could service the needs of recently imperiled communities of the faithful.

More recently a role reversal has taken place. While non-Hasidic Haredi yeshivas continue to emphasize theoretical Talmudic learning over practical rabbinics during regular study periods, they and their Jerusalem affiliates have increasingly developed and supported auxiliary programs dedicated to training rabbis (and their wives) so that they can reach out far beyond Orthodox boundaries. RIETS, meanwhile, focuses most of it energies on inreach—servicing the highly specific intellectual and ideological needs of its natural constituents, observant Jews. Indeed, in the past few years it has offered an option for rabbinical candidates to train to serve as outreach specialists. Paradoxically, however, the program is funded and orchestrated by the Haredi oriented Ner LeElef, that specializes in training Haredi outreach activists.

If the evolution in Haredi Orthodoxy reflects a distancing from strict sectarianism, the core Modern Orthodox versions exemplify a retreat of this sector inward toward survivalist mode. Many within the Modern Orthodox camp now admit to the lack of well-defined ideological principles and charismatic leadership. Some children of Modern Orthodoxy have responded by moving closer to the more doctrinaire Haredi Orthodox approach, while others have been attracted to other social and intellectual frameworks that have led to a weakening in their Jewish observance and religious involvement. Whichever the case, the common result has been a sense of “crisis” that has been articulated by Modern Orthodoxy’s strongest supporters and leading ideologues.

The changes that have occurred within American Orthodoxy have resulted in a more fluid and less easily categorized religious stream than that described by those outstanding academics who initially studied American Orthodoxy in the mid-1960s. Like any religious trend it is variable and continues to evolve in response to changing internal and external realities.

3) How did Kiruv change Haredi Orthodoxy?

The key position that outreach now occupies within the formerly “sectarian” “yeshivish” Orthodox ethos points to a basic change that began to emerge within this sector in the late twentieth century. The more confident the leaders were that their style of Orthodoxy was not threatened with extinction, the more sensitive some of them became to the sharp increases in assimilation and loss of Jewish identity around them. Indeed, they may have seen outreach as a tool for strengthening their own groups through “mass conversion” of the non-observant. Yet, these trends taking place within Haredi Orthodoxy move beyond mere efforts to draft more adherents.

Rather than simply aiming to bring new recruits into their own ranks, there is a growing appreciation for positive expressions of Jewish identity on the part of the broader Jewish collective, even if they do not lead to adoption of an Orthodox lifestyle. In tandem with the novel efforts, various institutional boundary markers that were considered sacrosanct in previous generations— such as the height of the barrier between men and women in the synagogue, not entering a Reform synagogue even to teach Judaism, strict separation between sexes in social and cultural settings, non-participation in certain types of secular or popular oriented recreational and public events —have been traversed or blurred in the effort to engage other Jews.

There are also growing economic incentives for the Orthodox to adopt a less combative approach and even congenial approach to other denominations and to the broader Jewish community. As the Haredi yeshivas produce larger pools of graduates, the pressure to generate employment opportunities for individuals who possess rich stores of religious knowledge but minimal secular education has increased dramatically. Today, for example, there are nearly 6500 full-time students in Lakewood’s Beth Medrash Govoha. With an average stay in the institution of six to seven years, more than 500 alumni enter the work force each year.

The Orthodox outreach “industry” has opened new vistas for Haredi employment. By lowering the internal Jewish tensions, then, more opportunities to market their outreach products are made available to the kiruv workers.

Another financial motivation for the Orthodox to adjust their approach to the non-Orthodox is the need to secure funding for specific programming. As Haredi institutions have expanded, they have increasingly looked to earn capital grants awarded for specific projects by nonsectarian frameworks. As one of the conditions for their support, these organizations often demand that those being funded refrain from polemics and demonstrate their commitment to Jewish unity.

The majority of American Haredi Jewry do not necessary have direct exposure to the boundary crossing changes described in my book, as they remain rooted both geographically and culturally in the enclaves spread all over Brooklyn and Rockland County in New York, in Passaic and Lakewood in New Jersey. Nonetheless, the influence of the outreach ethos and practical leniencies on these sectors filters down way beyond the actual activists themselves; in the course of the exposure of their extended families to new environments and locales during visits and lifecycle events, via the numerous programs for training outreach professionals and facilitating their programming that are advertised and often based on yeshiva campuses and in Haredi publications, and through the transformation of “kiruv” superstars into Haredi role-models.

4) How have Modern Orthodox “gap year” pilgrimages to Poland gravitated toward a Haredi model?

Since the 1990s, 8-10 day seminars to Poland have gained a central place in the menu of educational experiences offered to Orthodox students spending their gap year in an Israel-based Torah establishment. The trip to Poland takes place in the context of a year in which they have detached themselves—almost always for the first time in their lives—from their parents’ homes and watchful eyes and become exposed to all-encompassing environments led by charismatic, spiritually oriented individuals.

During this period abroad, students are often exposed to a holistic brand of Orthodoxy that questions the ideals of Americanization and acculturation once championed by Modern Orthodoxy. In addition, some Israeli Religious-Zionist yeshivas that support the State of Israel and send their students to serve in its army are nonetheless highly critical of secular culture and its educational premises. Their tendency is often toward strict interpretations in matters of halakhah, except in areas that relate to the Zionist enterprise. There are also many products of Modern Orthodox homes and schools who attend yeshivas in Israel staffed by American immigrants who have adopted a Haredi lifestyle and are eager to thrust their students in this direction as well. Undoubtedly, there are certainly prominent and popular Israeli yeshivas and seminaries that do not fit neatly into this overall description.

The immersion that is experienced during the weeklong seminar in Poland does not in and of itself cultivate new identity formation. It is rather an agent, albeit a uniquely potent one that can complement or concretize processes that have already begun, or even set in to motion new ones.

The numerous encounters with the locations in which Nazi persecution and systematic murder led to so much Jewish suffering, is wrought with tension and emotional intensity. The students remain with their groups during the entire trip, under the supervision and charge of knowledgeable, compelling, and often spiritually driven educators, who perceive the seminar as a unique environment for disseminating religious ideals. Some even refer to it as a “journey toward holiness.”

Like Victor Turner’s now classic description of the pilgrimage, then, the Poland trips for American Orthodox yeshiva/seminary youth represent a phase in which one is separated in space and time from normal social frameworks and their limitations. Yet rather than isolated events with limited long-term influence, these pilgrimages to Poland—which take place at the end of the winter–spring term, when students are generally at their most enthused and motivated—actually serve to solidify lessons learned throughout the year.

These programs have gradually adopted rules and changed educational concentrations such that the overall tenor is much closer to the prevailing Haredi perception of pre-war Eastern Europe and the Holocaust than the more diverse approaches that characterize Modern Orthodox discourse on these subjects. Once a coeducational endeavor, today strict separation of the sexes is enforced to the degree that male and female delegations may not visit the same concentration camps simultaneously. On an ideational level, Jewish solidarity and the diversity of pre-War European Jewry, once core themes, are no longer central motifs on such seminars. In parallel, over time considerably more emphasis has been placed on connecting students to an idealized world of prewar Torah luminaries and Hasidic masters. Two locations that serve, for example, as focal points for this type of experiential education are the gravesite of the early Hasidic master, Rebbe Elimelekh of Lezajsk and the former court of Gerrer Rebbe in Gora Kalawaria (adjacent to Warsaw).

To be sure, other aspects of the Modern Orthodox seminars, such as centering the program on the destructive events of the Holocaust and supporting Zionist perspectives regarding postwar Jewish life, remain firm.

5) How did Rabbi Herschel Schachter create a new heresy?

Rabbi Schachter has been responding vociferously in writing to various ritual initiatives of Orthodox feminism since 1984, when he together with four other RIETS rashei yeshiva published a responsum forbidding participation in women’s prayer groups. All of his relevant discussions during the late twentieth century were rooted in his perception of a direct relationship between Orthodox feminist proposals and the “slippery slope” of adopting behaviors associated with the Reform and Conservative movements. (For Ferziger article, see here. )

This focus on interdenominational boundaries changed in 2003, when he published an essay titled “On the Matter of Masorah,” in which Reform Judaism is not the main culprit, but merely one among a long line of heresies that, according to Rabbi Schachter, now includes Orthodox feminism.

The initial theme in the essay is the significance of masorah—longstanding traditions of handed-down religious behavior—for deciding normative Jewish law, even when the textual sources may allow for alternative rulings. He then applies this principle as the basis for prohibiting public Torah recital by women, a novel practice that had risen to the forefront of Modern Orthodox debate.

In a certain sense, Rabbi Schachter’s utilization of “masorah” as a tool for ruling on normative observance is not unlike the authority given for many generations to minhag (custom) as a basis for the correct religious behavior. That said, minhag may provide justification for conduct that does not seem to be consistent with textual sources, but it does deny the theoretical correctness of the interpretation derived directly from the text. Masorah, on the other hand – as articulated by Rabbi Schachter, not only specifies the correct behavior, it nullifies the possibility of acting differently or even identifying the existence of an alternative approach, even if there exists a strong textual basis for doing so.

Toward the end of his essay, Rabbi Schachter reinforces his prohibitive ruling by depicting a “historical tradition” relating to women and Judaism: “The Tzedukim [Sadducees] were apparently bothered with the fact that the Torah discriminated against women regarding the laws of yerusha [inheritance], and they attempted to “rectify” this “injustice” somewhat. In later years the early Christians adopted several of the positions of the earlier Tzedukim…Several centuries later, the Reform movement continued with this complaint against the tradition, that the rabbis were discriminating unfairly against women by having them sit separately in the synagogue, etc. This complaint has developed historically to become the symbol of rebellion against our masorah. The fact that this symbolizes harisus hadas [destruction of the religion] causes it to become a prohibited activity.”

In this narrative, which is unprecedented among Orthodox authorities, feminists have not simply followed the path of their Reform and Conservative contemporaries. Rather, through their behavior they had declared themselves direct heirs to the heretical groups who deviated from normative Judaism since ancient times. For beyond any other areas of dispute with the rabbis, according to Rabbi Schachter, the complaint that linked all these historical heresies was discrimination against women. As such, anyone who raises objections to accepted rabbinic policy on this topic is clearly aligned with the deviant legacy and intent upon destroying the religion.

During the following year, 2004, Rabbi Schachter published an essay “Can Women Be Rabbis?” in which attacked the new custom of inviting a learned woman to recite the text of the ketubah (marriage writ) under the wedding canopy. Following the masorah thesis, he argues that the fact that there is no law which requires a male reader for the ketubah, does not automatically mean that having a female one is consistent with other hallowed values that emerge from the halakhah. Here, once again, Rabbi Schachter returned to comparing Orthodox feminists with classical heretics through the common goal of destroying rabbinic Judaism: “Clearly the motivation to have a woman read the kesuba is to make the following statement: the rabbis, or better yet—the G-d of the Jews, has been discriminating against women all these millennia, and has cheated them of their equal rights, and it’s high time that this injustice be straightened out. . . ”

In 2014, Rabbi Schachter revisited this “heretical narrative” for the third time in a nine-page Hebrew responsum that declares “partnership minyanim” to be unequivocally forbidden. Once again, he states that the motivation behind much of the contemporary actions is the sense that the rabbis have historically discriminated against women. Such claims, he warns, can be traced to the Sadducees who disputed the Sages’ understanding of the Torah during the Second Temple period, and subsequently to the early Christians.

In Rabbi Schachter’s references from 2003, 2004, 2014, together with the Sadducees and Christians, the Reform and Conservative movements constitute factions that found their roots in Jewish tradition, but whose theologies and religious behaviors had placed them irrevocably—in Rabbi Schachter’s opinion—beyond the framework of normative Judaism. By associating the claims of the Orthodox feminists with them, he declared that they too were destined for a similar fate. I suggest that in associating Orthodox feminism with other historic heresies, Rabbi Schachter sought to clarify that feminism was not just an issue for debate, but it had become the central litmus test for whether a group or institution could be remain part of the Orthodox spectrum.

6) What revolution is taking place in the role of women in Haredi Orthodoxy?

It has been assumed that Haredi Orthodoxy was relatively immune to the trends of feminism and gender egalitarianism. In recent years greater attention has been drawn to the emergence of new types of Haredi female figures. Chabad women emissaries constituted one of the first groups to draw notice in this transformation.

My book highlights parallel and unique trends among non-Hasidic Haredi women. There is a “silent” revolution taking place in which Haredi women are increasingly taking on more prominent religious leadership roles. One of the main frameworks for these transformations is the field of outreach. The rise of the female outreach activist is an additional manifestation of the ways that Haredi Orthodoxy’s abandonment of sectarian approaches to nonobservant Jews has led to less rigid religious and social norms on the part of members of its core constituency. The new functions taken on by female outreach activists raise conflicts and engender complex hybrid identities that digress in notable ways from accepted notions within this sector.

Interestingly, despite certain parallels with the new positions – such as “spiritual leader” advanced among Modern Orthodox feminists, to date there has been little public criticism by Haredi leaders of the novel figures within their own camp. I suggest two explanations for this seeming passivity. First, while social boundaries have been traversed, the Haredi female initiatives have avoided the area of ritual and prayer. Thus, the public sanctum has not been challenged. Alternatively, the rise of the Haredi female leaders may account in part for the virulent condemnations by Haredi officials of Modern Orthodox feminist initiatives such as partnership minyanim. The main goal of attacking the Modern Orthodox efforts so vigorously, then, is not to dictate Modern Orthodox behavior but to clarify the limits of “Haredi feminism.”

7) How are Haredi activists and YCT graduates more similar to each other than to the RIETS products?

Ironically, from a professional perspective the liberal YCT rabbi actually has more in common with Haredi outreach-oriented figures than the inreach focused RIETS graduates. YCT rabbis are to a great extent, like their Haredi outreach counterparts (along with Chabad), specialists who gravitate to peripheral Jewish communities that lack a strongly-rooted Orthodox infrastructure. Neither of these cutting-edge rabbinical products would reject more “mainstream” congregants, but the skill sets and outlooks that they internalize through their rabbinical training tailor them to attract and address the concerns of the wider Jewish community. To be sure, the YCT and Haredi worldviews diverge dramatically on multiple issues. Yet both frameworks demonstrate that in order for Orthodoxy to deliver a relevant message to the majority of American Jews it must cultivate environments and train leaders who are in touch with the needs of this body.

Notwithstanding the common denominators, it is important to reiterate the distinctive backdrops that led to the emergence of the new Haredi and YCT rabbinates. The Haredi “outreach specialist” training programs emerged as manifestations of strength. The vastly improved self-image of a triumphant Haredi Orthodoxy has engendered the creation a new type of rabbi. One who feels that he can afford to concentrate on dealing with issues that stand outside the immediate concerns of his own community.

YCT, in contrast, came about because prominent Modern Orthodox leaders sensed a weakening in the ideological fiber of their core constituency. Its main justification for existence is to serve as a corrective to what is seen as a Modern Orthodoxy gone astray. In this context, part of the attempt to reformulate its priorities is the need for greater involvement with the weakly affiliated Jewish population. But this is not necessarily an expression of vitality. It stems from a conviction, rather, that without this element American Modern Orthodoxy is lacking a crucial ideological mandate that was for many years at the root of its own self-identity.

The idea that this common “outreach” principle could forge a bond between the ideologically polar but similarly innovative elements within American Orthodoxy based on a shared broad constituency discourse is tantalizing. That said, the chapter in the book on Chabad and Haredi outreach activists, suggests that on a practical level such commonalities more often than not sharpen competition rather than afford a sense of shared mission.

8) How has the emergence of YCT/Maharat impacted on the realignment?

The controversies surrounding YCT, Open Orthodoxy, and Orthodox feminism are expanding and accelerating the realignment of American Orthodoxy. Throughout most of the book I present the move to the right of Modern Orthodoxy and the shift to greater outreach and decline of Haredi sectarianism primarily as parallel but not interdependent phenomena that have reached a certain degree of confluence. The rise of Open Orthodoxy and the sharp criticism it has received both from the RCA and the Haredi world has recently facilitated a more synchronized coordination.

To offer just two examples: As part of an effort to vilify Open Orthodoxy, in 2014 Agudath Israel spokesman Rabbi Avi Shafran offered a relatively broad list of who does fit in to the Orthodox rubric that exemplifies the postsectarian realignment examined in my study:

An adherent of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, a Satmar chassid, a ‘Litvish’ yeshiva graduate and a student of Yeshiva University’s Rabbi Isaac Elchonon Theological Seminary are all unified by the essence of what the world has called Orthodoxy for generations. But ‘Open Orthodoxy,’ despite its name, has adulterated that essence, and sought to change both Jewish belief and Jewish praxis.

Taken in light of past Haredi attacks on Yeshiva University as well as Chabad, this is quite a historic document.

Similarly, Rabbi Yitzchak Adlerstein, a moderate Haredi figure, responded to Rabbi Schachter’s strong ruling against partnership minyanim with this comment:

Rabbi Schachter’s piece is a wonderful contribution. There are tens of thousands of Orthodox Jews in the Modern Orthodox world (and certainly in the Haredi world) who view the tearing down of all barriers by YCT and Open Orthodoxy with horror… Rabbi Schachter’s presentation ought to be a wonderful beginning. This will be more important in the long run than the existence or disappearance of partnership minyanim. It will not be enough to take Rabbi Schachter’s formulation and use it to rally the troops. The challenge will be to take it and build upon it, at least to those who do not reject the idea of contemporary rabbinic authority. Before this essay, making the case for limitation was an issue of each rabbi for himself. Rabbi Schachter’s contribution could allow for a common platform upon which others can build and explain… that can be shared by the entire community, excepting the outliers.

These declarations exemplify Emile Durkheim’s now-classical explanation from 1892 of the role of deviance in society, “the deviant act then, creates a sense of mutuality among the people of a community by supplying a focus for group feeling. Like a war, a flood, or some other emergency, deviance makes people more alert to the interests they share in common and draws attention to those values which constitute the ‘collective conscience’ of the community.”

Having said this, the future of Open Orthodoxy and for that matter a less Haredi-sympathetic Modern Orthodoxy all together, may be determined just as much by geographic and economic considerations than by clarifying theological beliefs and synagogue standards. Even if Haredi Orthodoxy has expanded its reach and language of discourse, it still remains concentrated geographically around a few locations in Brooklyn and Rockland County in New York, Lakewood and Passaic in New Jersey, as well as smaller but considerable representations in Baltimore, Cleveland, Chicago, Toronto, and Los Angeles.

At the same time, an active and significant group of Orthodox Jews still exists that—regardless of whether they resonate with the ideals of Open Orthodoxy—sees cross-cultural interaction and secular education as part of an ideal. For many of these Orthodox Jews, YU is their standard for a Modern Orthodox institution. Even if they do not necessarily approve of all the innovations associated with YCT and Open Orthodoxy, they may sympathize with some of its core ideals—especially those related to gender—and appreciate its place within the broad spectrum of American Orthodoxy.

At this juncture it is premature to declare that Modern Orthodoxy will disappear as a distinctive educational ideal and lifestyle. Indeed in the end Modern Orthodoxy’s future may be primarily a function of its financial feasibility far more than its capacity to inspire ideologically allegiance. According to the 2013 Pew Report, the Modern Orthodox have the highest per-capita income of all American Jewish sectors (37 percent earn over $150,000) and also have the largest percentage of college graduates (65 percent) and are the most attached to Israel (79 percent). Living within the Modern Orthodox community—joining its synagogues, educating children, sending them to camp, visiting Israel, as well as covering their college and graduate school tuitions—is an especially heavy economic burden. Were there to be a major financial upheaval, Modern Orthodox families and institutions would be particularly vulnerable to these changes.

9) What do you think American Modern Orthodoxy needs for the next decade?

The ongoing vitality of any religious movement depends upon its ability to sustain for its adherents a sense of collective purpose and meaning. The specific issues that preserve group identity can evolve over time; sometimes the focus may fall on positive principles, sometimes on opposition to rival factions or theologies. When the driving assumptions are clear and inspiring, internal differences can be overcome. But when ideological inertia sets in, differences tend to become inflated and to portend rupture.

For over two centuries, factions loosely assembled under the “modern” Orthodox rubric came together around three main principles that were seen merely as pragmatic compromises. First, a full commitment to religious observance does not demand reclusion from the broader society or from secular knowledge. Second, while personal observance is the ideal and should be encouraged, it is not an unconditional requirement for individual membership in the Jewish collective. Third, neither Reform nor Conservative Judaism is a legitimate expression of Jewish theological teachings.

Historically, there were sharp internal debates about these principles as well as multiple interpretations of them. But there was also overwhelming consensus on the foundational ideals that inspired Modern Orthodoxy, and that distinguished it both from liberal denominations and from sectarian forms of Orthodoxy.

If, at the heart of today’s Modern Orthodoxy, one finds only a common “lifestyle”—what Jay Lefkowitz has dubbed “social Orthodoxy”—part of the reason may lie in the weakening hold of its foundational vision on the allegiances of the spectrum of its adherents. Today, by contrast, haredi circles increasingly accept higher education and cooperate with non-Orthodox denominations under the banner of combating assimilation. Still, the norms of haredi Judaism remain clear-cut and well defined, while the nuanced messages of Modern Orthodoxy become harder to detect.

Not long ago, certain causes—a striking example being the activist campaign on behalf of Soviet Jewry, a movement in which the Modern Orthodox took a leading part in mobilizing the energies of the entire American Jewish community (and to which a chapter in the book is devoted)—continued to nurture a sense of shared and distinctive purpose.

What themes continue to galvanize America Modern Orthodoxy today? Commitment to the State of Israel as a religious value is still an ideal that joins together the different factions and generates considerable enthusiasm. But those most passionate about Israel tend to move there in order to contribute more directly to the society’s welfare as well as to experience a less bifurcated Jewish life, and this causes American Modern Orthodoxy to lose some of its most capable and inspired offspring.

This brings me back to the evolving religious role of women: the one issue that continues to spark serious excitement and debate among both those who campaign for expanding opportunities and those who oppose far-reaching changes. Whether equilibrium can be achieved on this issue, and can be accepted by the broadest part of the constituency, is unclear.

What is clear is that the ongoing vitality of American Modern Orthodoxy, and ultimately its survival, will depend upon the emergence of new causes or visions that generate pride and solidify a broad identification not just with the movement’s “lifestyle” but with its distinctive religious outlook.

10) What was your biggest surprise in your research?

Among my biggest surprises during my field work were: discovering community kollel-sponsored annual golf tournaments, kiruv Super Bowl parties advertising beer on tap, and that the key to Haredi outreach activists being able to meet students and non-Orthodox colleagues for learning sessions over coffee at Starbuck’s was the decision some years back by the latter to offer soy milk based latte’s and cappuccino’s – thus alleviating the “cholov yisrael” problem.

11) How will the sexual and financial scandals affect the community?

Tragically, over the past decade numerous sexual and financial scandals have come to light across the spectrum of American Orthodoxy. They are troubling to anyone who, correctly to my understanding, perceives moral fortitude as a central mandate for committed religious Jews. Their deepest direct impact is, however, upon the specific communities and individuals who held the religious leaders involved in esteem and were personally connected to them – often in very positive ways.

However, fundamental questions are raised by the fact that banner institutions and their leaders were aware at some level of the abuses and whitewashed them and did not confront them straight on. But these do not necessarily relate to ideological issues as much as to a basic stumbling block within organized religion. Namely, the difficulty to balance between the main goal of religion-which is serving God- and the need to create and sustain religious institutions -that inspire and disseminate religious ideals. Too often, maintaining the “edifice” takes precedent over securing the values. Turning the other way when unethical behavior of prominent individuals are discovered out of fear that the scandals will damage the religious or educational framework is a prime example.

It would appear to me that the main lessons to be learned are not that there is any innate connection between the aberrant behavior of individuals and the theological foundations of the movements with which they associate. Rather, to first acknowledge that religious institutions, like all contemporary public frameworks (corporations, universities, government offices, hospitals) will more likely than not be populated by a certain minority of deviant persons who use their authority and esteem as tools for illegal and/or immoral activity.

Therefore, religious movements cannot simply create internal safeguards. They should contract with outside, independent bodies, that specialize in this type of security and will not be swayed by personal connections to the perpetrators or fear of damage to beloved institutions. The more realistic and pragmatic the approach is to these issues, the less they will eventually blow up into major public scandals.