There is a mild debate in Israel over a little introduction to medieval thought published by Prof Shalom Sadik who advocates a Maimonidean rational naturalism and Rabbi Shmuel Ariel who presents a religious critique

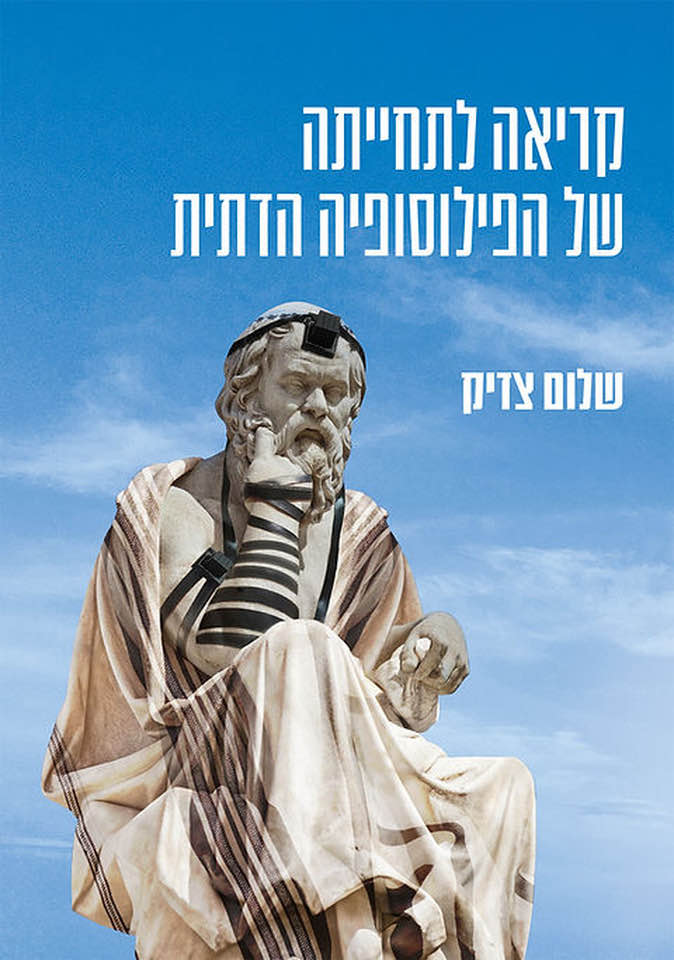

Prof Sadik in his book A Call For The Revival of Religious Philosophy. [Hebrew] (Keriah le’techiyah shel Hafilosofia Hadatit), a related English book by Sadik came out last year Maimonides A Radical Religious Philosopher(2023)

Sadik presents many of the basics ideas of the Guide of the Perplexed as an esoteric document: the eternality of the world, that miracles are natural events, that God does not violate the course of nature, providence is naturalistic, and Mosaic prophecy is an act of his own cognition. These are standard understanding of the Guide debated by Samuel Ibn Tibbon, ibn Falquera, Albalag, Efodi, Narboni, Anatoli, Gersonides, and other Maimonideans/Averroists within Jewish thought. These are also affirmed by most modern scholars of Maimonides’s thought.

In contrast, Rabbi Ariel assume that these ideas are outside of the limits of accepted Jewish thought, that mizvot assume that one is doing them to serve a theistic God, and that Judaism is primarily about belief in the principles of Judaism. These ideas should certainly not be taught at yeshiva.

Prof Sadik points out that Crescas and Albo already show that we do not exclude people for their philosophic beliefs. However, Sadik points out that much of Kabbalah as well as Hasidut would be outside the pale of Maimonidean thought as foreign worship since they contain the wrong conception of God.

Sadik and Ariel produced an unedited Hebrew document on their discussion, but there are more pieces of the discussion on social media.

This discussion produced long threads on social media debating the topic, but it was almost entirely about Hasidic thought and how the personified God who is moved by human action is the Jewish opinion and how now in our age Hasidut or Rabbi Kook is the horizon of Jewish thought along with a literal reading of the Bible and Yehudah Halevi’s Kuzari. Rav Nachman of Breslov has become the norm. It was as if no one knew about Maimonides and the method that medieval Jewish thought treated the Bible in a way to remove the literal anthropomorphism.

What really struck me, was that it seemed almost no one had heard of the medieval thinkers, as if no one knew the Guide of the Perplexed and its esoteric teachings and the assumption that these medieval thinkers were not part of the canon of Jewish thought. Yet, these texts and ideas are taught in every department of Jewish thought. They are a pillar of mastery of Jewish philosophic texts. No one on social media could offer a defense of medieval theistic naturalism or understood how important they are for understanding Jewish thought and intellectual history.

In order to present the issue, I asked six experts on medieval Jewish thought: Do you see the medieval Jewish rationalists and naturalists as them as important for Jewish thought and thinking? How important are medieval rationalism and the Maimonidean/Averroiest Jewish commentaries. I asked each participant for just two paragraphs so that you get a taste of the diverse justifications of these thinkers. Those who answered were Professors Zev Harvey, Yehuda Halper, Daniel Rynhold, Sarah Pessin, Y. Tzvi Langermann, and Lawrence Kaplan. They are presented in the order in which they replied to my query. Go and Study.

From my perspective, these naturalistic ideas are already in Abraham Ibn Ezra’s commentaries, Shlomo Ibn Gabirol’s piyyutim, and Isaac Arama, Akedat Yitzhak. These works are certainly in the canon. And these ideas are needed to understand the dialectic in later works including Kabbalists such as Nahmanides, Yakov bar Sheshet, Maharal, Shelah, and the Vilna Gaon. In addition, these of works generated several Maimonidean controversies in 1230’s, 1288, 1300-1305, and then later in 16th century Eastern Europe. The study of these debates reveals the contours of Jewish thought.

Furthermore, these rational thinkers are studied to produce new Jewish thinking in every generation. They have produced many forms of Jewish thought including Kantian and Hegelian reading of Judaism, process theology, philosophic contemplation, theistic skepticism, theistic naturalism, and Barthian versions. Almost every generation returns to Maimonides and his commentaries to develop Jewish philosophic thinking.

Zeev Harvey, Emeritus Professor of Jewish Philosophy, Hebrew University

Radical Philosophy and Mainstream Judaism

The genius of Jewish Thought is its cosmopolitanism and pluralism. It is written in seventy languages and ranges from radical rationalism to radical mysticism. Maimonides, like Rabbi Shmuel Ariel after him, believed that Judaism can be defined by dogmas. However, as Mendelssohn said, the only truly good things that came from his 13 Principles are the beautiful piyyut Yigdal and the great books by Hasdai Crescas, Joseph Albo, and Isaac Abrabanel, which criticized those Principles and suggested different approaches.

It was Ibn Gabirol who brought radical philosophy into the Synagogue with his Adon Olam, Azharot, and Keter Malkhut. Ibn Ezra and Gersonides brought it into Mikraʾot Gedolot. Maimonides’ Guide of the Perplexed is the most influential book in Jewish philosophy, and traditional Jews usually read it in Ibn Tibbon’s Hebrew translation, together with the radical Commentaries of Narboni, Kaspi, and Efodi. The presence of radical philosophy in mainstream Judaism is clear and significant.

Last February I was invited to give a series of seven shiʿurim on the philosophy of Rabbi Hasdai Crescas at the “Kerem” center in Brooklyn. Founded by Reb Joel Wertzberger and directed by Harav ha-Gaon Yonoson Marton, “Kerem” is a group of Satmar rabbis and scholars who are wholly committed to the Satmar derekh, but interested in learning about different approaches. Among other Israeli academics who have spoken there are Moshe Halbertal, Yair Lorberbaum, Benjamin Porat, Elhanan Reiner, and Shai Wozner. James Diamond of Canada has also spoken there. I was not surprised to find that the Satmar ḥasidim were well versed in Sefer Or Ha-Shem and other medieval philosophic books. However, I was surprised when they asked me pertinent questions about the most recent writings of young Israeli scholars – not only Shalom Sadik but also more controversial authors, like Micah Goodman and Israel Netanel Rubin. I have no doubt that in the eyes of the Satmars Rabbi Ariel’s belief that the State of Israel is atḥalta de-geʾulah is far more problematic than Professor Sadik’s views on hashgaḥah.

Yehuda Halper, Dept of Jewish Philosophy. Bar Ilan University

Following Al-Farabi and Averroes, medieval Jewish philosophers turned to Aristotelian logical works to develop a notion of what modern logicians call second-order knowledge. This kind of knowledge is knowing that you know something. Al-Farabi had associated the Aristotelian demonstration, the pinnacle of logical argument and the foundation of mathematical and scientific reasoning, with certainty, i.e., knowing that you know what has been demonstrated. Thinkers of the Ibn Tibbon family and later commentators on Aristotelian thought adopted the demonstration as the ideal basis for math and science, but recognized that there are very few, if any proper demonstrations in Biblical or Talmudic works. Rather what we might find in those works are portrayals of beliefs whose verification is less than certain. They often looked to other forms of argument, such as dialectic, rhetoric, and poetics, to describe the arguments of such works. That is, thinkers like Jacob Anatoli and Moses Ibn Tibbon, focused on the form of Biblical and Talmudic claims and took them as non-demonstrative, but often persuasive by using other forms of argument. Using these techniques they were able to differentiate in fairly technical terms argumentative techniques for religious and scientific purposes.

Students today often think of belief as something inherently irrational, as essentially opposed to scientific or justified knowledge. As such, they seem to think that people cannot reason about belief. The medieval Aristotelians exemplify ways in which humans can reason about belief, even beliefs that are not scientific or scientifically provable. In fact, I believe that everyone can benefit from greater use of reasoning, in public, in private, about religion, about science, in general.

Daniel Rynhold, Dean & Professor of Jewish Philosophy, Yeshiva University

It’s difficult to attribute immense historical importance to the thinkers you mention since they are little studied by the Jewish masses. Some are likely unknown to the average yeshiva bochur, and even in the academy, with the possible exception of Gersonides, they are only studied by specialists in medieval thought. However, they are incredibly important (again, particularly Gersonides given that his biblical commentaries place his works – even if unopened – on the shelves of many Batei midrash alongside the classical and oft-studied commentators) for modelling a path for a relatively silent but sizable enough minority in the Orthodox Jewish world. And that path is one that allows halakhic study and commitment to sit side by side with a theology that veers far from the mainstream. It troubles me when such approaches are not accommodated. It’s not that those opposed to such philosophies need to accept them. But however difficult it is for some to understand how those non-mainstream philosophies can support halakhic commitment, for people of a certain religious sensibility, it is only those theologies that can inform their religious commitments. One person’s heresy is another’s “divrei elokim hayyim” as anyone who has, for example, read both Ramban and Rambam can attest.

Sarah Pessin, Professor of Philosophy, University of Denver

The question of rationalism in a thinker like Maimonides is itself wrapped up in a pre-modern sense of ‘the rational’ where ‘the rational’ includes a depth of commitment to logic, math, and science, yes, but all at once also to ethics and theology. It’s a wonderful Greco-Islamo-Jewish framework for seeing the hand of God and with it the heart of divine wisdom in the details of botany and also in the invitation to minister with respect to neighbors. Living a life b’zelem, in this context, is living a life which aspires to a hint of God’s wisdom and a trace of God’s goodness all at once such that a life of Torah and a life of science and life of ethics are all intertwined parts of a life-with-God.

Yes Torah—and yes Torah because yes wisdom and ethics; for the attentive person-of-God, the Torah is a gift just as our God-given talents of intellect and virtue are gifts. When in doubt, the Torah guides—but if the Torah appears to guide against reason and virtue, it’s a fine indicator that we’ve made a wrong turn.

While different in epistemological frameworks from a modern thinker like Buber, I think Maimonides would agree with Buber’s take on “theomania” as the error humans make when we are so excited to meet God (or relatedly, so confident that we have already met God) that we feel confident overlooking responsibilities to neighbors. I think Judaism–and also, humanity in general–is richer for Maimonides’ ancient sense of reason–shared by Greek, Islamic, Christian, and other thinkers–which features the sort of wisdom that imitates God’s wisdom not only of head but of heart, inspiring and inviting a life of religion-with-science-with-goodness-to-neighbors that mirrors the generosity of God’s overflowing hesed.

Y. Tzvi Langermann, Professor Emeritus, Bar Ilan University

It is impossible for me anyway to answer questions about relevancy without thinking about how the figures you mention are relevant to me, on a personal rather than professional level. I find inspiration and guidance in the thought of many figures across the cultures and ages, especially Maimonides. In this context the most important point is this: Maimonides wrote a guide for the perplexed–a book whose aim is not to inculcate doctrine but to show the way. It is fundamental to Judaism that there is only one Truth–with a capital T, because God is al-Haqq, the Truth, but each individual must make his/her own struggle or journey to approximate the Truth as best as one can. Maimonides’ chief aid is in coaching us how to avoid errors along the path.For this reason Maimonides, and not a few other medieval thinkers, are relevant–chief among them, Yehudah ha-Levi who, in my understanding, is no less rational than Maimonides.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating., Maimonides is clearly still relevant. The questions are how and why. To the best of my understanding of Maimonides’ historical setting and intellectual milieu, the question, rationalist or not, is out of place. Making this a focus of discussion is another example of the ubiquitous yet unavoidable act of imposing contemporary categories (whose parameters are not clear to me even in contemporary terms) on historical actors from another world. Yet this faux pas is unavoidable precisely because there is, for whatever reasons, great intellectual interest and, I submit, societal and political significance, in exploring the questions associated with rationality and its presumed opponents and slugging out the answers. Maimonides is brought into this exchange because his rich written legacy offers material for discussion and, yes, prooftexts, for the different positions–of course, when the material is translated (since most of it is in Arabic) and explicated. Finding support or at least solace in a towering authority (and yes, authority matters for everyone, admit it or not) certainly is helpful.

Prof Lawrence Kaplan, McGill University

For the radical Maimonideans, Maimonides’ view of the relationship between philosophy and religion is a prime example of what Prof. Carlos Fraenkel refers to as “philosophical religion.” That, Maimonides, to some extent, seems to be an adherent of philosophical religion is, in my view, undeniable. He identifies the highest and most profound teachings of Judaism, the account of creation and the account of the chariot, with the philosophical natural and divine sciences, and for him the highest and ultimate goal of Judaism is the knowledge, love, and fear of God based on reason. Moreover, Maimonides sharply differentiates between the welfare of the soul, correct beliefs in simplified or imaginative form prescribed for the multitude on the basis of authority, and perfection of the soul, the intellectual knowledge of God based on reason designed for the elite (Guide 1:33, 3:27).

And though he never says so explicitly, he intimates that observance of the commandments of the Torah, both commanded practices and commanded beliefs, inasmuch as they are accepted on authority, cannot endow one with perfection of the soul, though they can point one in the direction of attaining perfection of the soul, if one has the ability, through the use of one’s intellect.

Still, if one takes Maimonides at face value, it seems he cannot be viewed as an adherent of philosophical religion tout court, as say was Averroes. Here the radical Maimonideans, pushing Maimonides’ claim that the Guide is an esoteric work to its limits, argue that, despite his protestations, Maimonides in truth subscribed to the Aristotelian view of eternity and thus did not allow for the possibility of miracles understood supernaturally, whereby God suspends the natural order, even if only temporarily, through an act of will. Rather the biblical “miracles” are just wondrous acts, whose natural causes we do not understand. Along these lines and, more significant, for the radical Maimonideans such basic biblical doctrines as prophecy and providence have to be understood purely naturalistically, the more literal, personal, and supernaturalist presentation of these doctrines in the Bible just being an accommodation to the limited understanding of the multitude.

Unlike the radical Maimonideans, I see no reason to question Maimonides’ sincerity in affirming that creation is more probable than eternity. Still, I believe that one should not exaggerate the differences between the view that takes Maimonides’ affirmation of creation at face value and the radical Maimonidean view. For even according to the Maimonidean view of creation, the world is not just an expression of an act of divine will, but also of divine wisdom. This being so, the primary path to knowledge and love of God (See Hilkhot Yesodei ha-Torah 2:2) is not through knowledge of God’s miracles, as Halevi or Nahmanides maintain, but knowledge of God’s wisdom as revealed in the orderly and law-like processes of nature. And included in these law-like natural processes are the phenomena of both prophecy and providence which, for Maimonides, operate naturalistically.