What are the Lurianic Kabbalistic intentions? How do Lurianic kavvanot work and how does one read the baroque pictorial notations of a Lurianic siddur? This is a very technical interview, very detailed, geared for those in the know. This is my second interview with Jeremy Tibbetts on Lurianic Kavvanot. It is a continuation of his contribution from 10 months ago introducing the kavvanot in Siddur Torat Chacham, a Siddur Rashash by R. Yitzchak Meir Morgenstern

This great article was written by Jeremy Tibbetts, a rabbi, who is the co-director of OU-JLIC for Anglos in Jerusalem and is the Director of Education for Yavneh, an intercampus leadership program. He is a student at Hebrew University in Jewish Thought, intending to focus on the Rashash and kavanot.

In this introduction, he walks us through the conceptual development of the kavvanot, starting the journey with Rabbi Isaac Luria (The Arizal, 1534-1572) who moved to Safed in 1569, where he lived and taught for three years. In those final years, R. Chaim Vital (1542-1620) learned from him and devoted the rest of his life, spent largely in Damascus, to developing a proper exposition of Lurianic Kabbalah.

A century after Vital died, R. Shalom Shar’abi or the Rashash (1720-1777) head of the Yeshivat Beit El became a new link in the chain of Lurianic transmission, focusing on divine names and pictorial representations of the kavvanot. In addition, he focused on the immanence of the Eyn Sof in the practice. Finally, the Hasidic rabbi R. Tzvi Hirsch of Ziditchov or the Ziditchover (1763-1861) focused more on the human experience, more on the human transformation, and how we become transformed into the divine qualities.

- What are kavvanot?

Kavvanot are intentions to concentrate on when reciting the words of prayer or performing commandments (mitzvot). Often they focus on intangible realms and their particularities which are impacted by the kavvanot. The instructions are described in theoretical works or depicted in specialized prayer books. The Kabbalistic worldview hinges on the idea that the devotional mind can change the cosmos and the self at the same time.

Most people do not know about the kavvanot, due to access and accessibility. Regarding the former, the full set of Lurianic writings did not leave the land of Israel for over a century after Vital’s passing. As for the latter, Lurianic Kabbalah is extremely complex. Kavvanot necessitate erudite expertise in it and the ability to apply the most generalized principles and specific details of the system at once. Gershom Scholem considered Lurianic Kabbalah to be one of the most complex systems of thought in existence.

Kavvanot are not meant to undo or replace the simple meaning (pshat) of the supplications of prayer. Though one’s kavvanot take them to other realms, the practice must remain prayer fundamentally for it to work. Kavvanot work on the principle that as one gets to the peak of the experience, the more intentions there are to perform. The amount of kavvanot per word increases dramatically the more one prays.

2. For Hayim Vital, why do kavvanot?

Rabbi Isaac Luria told R. Chaim Vital that his kavvanot should focus on completing the worlds, yet at the same time, Luria understood the positioning of the worlds to directly impact human cognition and comprehension. These two aspects of completing the cosmos and attaining comprehension together are considered the fulfillment of humanity’s purpose.

For Vital, the ultimate outcome of kavvanot is to connect the light of the Infinite (Ein Sof) to our world, and then we need to draw it into vessels that can allow for non-overwhelming contact with infinite divine. Hence, “reducing the light is the ultimate intent of fixing the worlds (tikkun)” (Etz Chaim 9:4).

Kavvanot rectify the shattering of the vessels (shevirat hakeilim), whose broken pieces constitute our imperfect physical and spiritual reality. Our world is fundamentally broken, and as long as we do not do the fixings (tikkunim) necessary to fix it, evil and injustice will remain manifest. The tikkunim create partzufim, an infinite vessel made of ten sefirot which each contain ten sefirot and so on ad infinitum. These vessels, being infinite, can capture the light of the Ein Sof. Repairing these shattered vessels through kavvanot is the necessary prerequisite to making the light of the Ein Sof manifest within them.

This process of rectification followed by revelation also occurs within the individual. One grows spiritually as they perform the kavvanot, even in a semi-literal sense: they can fix and shine the light of holiness into the soul, and in their most idealized form, add completely new layers to it. Vital writes in Sha’ar haGilgulim that “when a righteous individual intends a complete and good intention (kavvanah), they can draw down a new soul” (Sha’ar haGilgulim Hakdamah #6).

There is a synchronicity between the completion of the worlds and of the self because the macrocosmic structure of the worlds and the microcosmic structure of the self mirror and influence each other. The fact that one of the names that Vital gives for the influx of Divine light into the partzufim is consciousness (mochin) is not coincidental. Corresponding to the upper sefirot of Chochmah, Binah, and Da’at, the mochin fill the “heads” of the partzufim before permeating the lower vessels too. As we strengthen and fill the partzufim, there is a direct impact on our consciousness in kind: “all of the forgetfulness that a person has is drawn from these lesser mochin. Whoever can, through their actions, draw them down below [to their proper place] by drawing in the greater mochin which push them… will have wondrous recollection in Torah and will understand the secrets of Torah.” (Etz Chaim 22:3).

This passage describing the interconnection between the ontological level of mochin and the commensurate mental outcomes of drawing them in was already considered extremely consequential in the early reception history of Lurianic writings.

- 3. For Vital, what is the difference between Intention (kavven) and envision (letzayer)?

Vital states explicitly that “one should intend” (veyikhaven) when describing daily prayer kavvanot. However, in a few places, such as in the intentions for the blessing after meals (birkat hamazon), he deploys a different term: “in the first blessing, from start to finish, envision (yetzayer) before your eyes [the Hebrew letters] aleph, lamed, hey” (Sha’ar haKavvanot Drushei Shabbat Seder Erev Shabbat) For each of the four blessings, one envisions one of the letters of the name ADNY spelled out. Letzayer is extremely uncommon in writings on kavvanot and extremely common in writings on yichudim. Both can be contrasted in Vital’s writings with changes in the worlds which occur without our intention automatically (mimeileh).

Lechaven is a specific type of intention. Vital writes that “you should intend and think in your thoughts” (Sha’ar haKavvanot Drush Kabbalat Shabbat #1). It occurs in the mind. These kavvanot are focused and thought-based but not imagistic. Kavvanah is an applied form of thought.

In normal waking life, thoughts pass in and out of our mind quickly with little perceivable consequence for the world around us. Kavvanot are the practice of taking thought and using it to affect the spiritual worlds like our hands would affect the physical world around us. As one contemporary commentator writes, “one must intend actively, not just think in their thoughts that the matter occurs of its own accord (me’eilav)” (Sha’ar Ruach haKodesh Im Peirush Sha’arei Chaim by R. Chaim Asis, Vol. 2 pg. 561).

The experiential impact from this focused type of kavvanah has two aspects. First, as discussed above, the actual technique of utilizing the focused intentional mind as an experiential component linking between the worlds’ spiritual states and our own cognitive states. One finds oneself at the bottom of a chain of divine illumination.

There is another aspect though, discussed in the recitation of the Kedusha, when many of the tikkunim of the daily prayers have been completed: “When saying ‘the world is filled with God’s glory,’ which is a secret of Malchut, intend [vatechaven] that we are the children of Malchut and we receive holiness from our mother. Therefore, intend to absorb yourself within Malchut to receive the holiness drawn onto her” (Sha’ar haKavvanot Drushei Chazarat HaAmidah #3). The ultimate type of kavvanah is not visual revelation but absorptive transformation. At its peak, one is no longer acting on the worlds as something external but as something internal.

We reclaim our place in the constellation of worlds and “when drawing the supernal holiness to the Blessed One,” one can “draw an aspect of this holiness onto themselves as well… they are sanctified and God is sanctified with them and within them” (ibid.). The focus on fixing the upper realms, in particular the lower partzufim and Malchut above all, is not a blockage to experience but a gateway to experience, a reveling in the intangible effusion of the divine.

- 4. Are Kavvanot individualized?

Kavvanot must be individualized. Vital writes that he was instructed to intend based on where his “soul is drawn from,” and so he must intend through one kavvanah particularly, and not the others” (Sha’ar haKavvanot Drushei Pesach #11). So too, the practice of meditating on combinations of divine names (yichudim) requires that one intend “according to their soul root” (Sha’ar Ruach haKodesh Yichud #12), expressed by punctuating the names differently.

This elevated type of knowledge, to identify the roots of different people’s souls, is exceedingly rare: R. Chaim Vital records that even great Kabbalists such as the Alshich, R. Eliyahu de Vidas, and Vital himself relied on the Arizal to inform them of their soul’s root. This could be conveyed in very basic terms, as one of the ten sefirot; more complexly as corresponding to a body part of Adam haRishon, who contained all souls in his pre-sin state; or more convoluted still, as part of a chain of prior reincarnations whose challenges in life recur and contour the tikkunim incumbent on them, such as when Vital writes that “the spark of Rabbi Akiva is closest to me out of all, and everything which happened to him happened to me” (Sha’ar haGilgulim Ahavat Shalom ed. pg.157).

In addition, the practice of kavvanot necessitates attention to our situational context and the world outside of us. If we do not pray with people who we are close to and whose challenges in life are understood intimately by us, the Arizal states that our prayers “will not bear fruit” (Sha’ar haKavvanot Drushei Birkot haShachar). Time and locale affect the mystical formulae of kavvanot.

- 5. What is the role of simchah in kavvanot?

Joy (simchah) has a central role in the efficacy of kavvanot. Vital writes at the beginning of Sha’ar haKavvanot Drushei Birkot haShachar that “it is forbidden for one to pray in sadness, and if they do so, then their soul (nefesh) cannot receive the supernal light which is drawn down to them at the time of prayer… the essential benefit and wholeness and attainment of the holy spirit depends on this matter.” One’s emotional state directly affects their soul’s ability to receive divine light.

Vital calls prayer the fulfillment of the mitzvah to “love your neighbor as yourself.” In particular, “if a person has knowledge and comprehension to know and be familiar with their fellow’s soul (neshama), and if there is something that is troubling their fellow, each one must join into their pain.”

6. Explain the three classes of kavvanot: perceptions, illuminations, and tikkunim.

Vital delineates three main classes of kavvanot and yichudim: hasagah (perception), he’arah (illumination), or tikkun. Yichudim of all three of these types are integrated into the practice of kavvanot,

The yichudim “to perceive some perception [hasagah]” (Sha’ar Ruach haKodesh Ahavat Shalom ed. pg. 39) center on a variety of prophetic practices and experiences that one can undergo. For example, these yichudim allow one who “has an awakening due to a soul which speaks with them… and doesn’t have the strength to bring out words from potentiality to actuality” (ibid., pg. 14). In another yichud in this section based on the name of the angel Metatron, Vital proscribes one to “close and shut their eyes and to isolate themselves [titboded] for one hour, and then intend to this yichud” (ibid., pg. 16). This also includes yichudim performed on the graves of righteous individuals to allow for “the cleaving of your soul to their soul” (ibid., pg. 33). At the height of this technique, one intends to sacrifice their soul, “raising up your soul combined with the soul of that righteous one” (ibid., pg. 34). When the hasagot of the Arizal are discussed in this work, they relate to his access to supernatural knowledge, such as the appearing of Hebrew letters on individual’s faces which indicate their merits or iniquities, dream interpretation, or the ability to learn secrets from the chirping of birds and the beating of a person’s heart (ibid., pgs. 51-61).

The second class of yichudim “clarify and illuminate [ta’ir] one’s soul to be a ready vessel to receive the supernal light continuously” (ibid., pg. 39). These yichudim are introduced by discourses on perfecting one’s character traits and ritual observance. These techniques strengthen the connection a person has to their individual soul, such as yichudim in which one contemplates being made in the tzelem Elohim [divine image] and how the body is constructed from divine names (ibid., pgs. 43-44). These yichudim utilize the soul as a bridge to greater experiences of spirituality and sanctity, like intentions to draw the sanctity of Shabbat into each weekday (ibid., pg. 45).

The third class “were given to human beings to repent” (ibid., pg. 61) and delineate the cosmic and individual impact of one’s transgressions. In these yichudim, Vital often records both an explanation of the disrepair caused in the worlds by a given transgressive act and then prescribes a series of penitential practice like fasting or rolling in snow alongside yichudim that one must perform. Gematriot [alphanumerical values of letters] feature prominently. For example, the tikkun for anger requires undertaking 151 fasts, the gematria of anger in Hebrew. During these, one intends to a form of the divine name Ehyeh which has a gematria of 151 as well (ibid., pg. 73).

7. How are Kavvanot arranged?

There is an inner lexicon, logic, and grammar to the kavvanot. They flow sequentially one into the next and cannot be performed out of order or be changed. Texts on kavvanot enumerate a variety of cognitive acts that are acceptable. The intentional mind can do a number of acts. It can draw effusion down (hamshacha), raise up (Aliyah) nitzotzot from among the kelippot, integrate (lichlol) its own soul with a given spiritual structure to elevate oneself spiritually, and much more. For the Arizal, their transformative potential lay specifically in how they change the worlds, a byproduct of which is a shift in human cognition.

One should nor pick single kavvanot out of theit logic and grammar. However, there is a machloket (disagreement) between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Kabbalists: the former say that whenever one learns a kavvanah they should begin to utilize it, while the latter say that one should only start practicing after having covered the entire system (Rav Morgenstern’s Netiv Chaim pg. 34). But both would look down upon any method of learning which focused exclusively on meditating on the self and which would exclude the change to the worlds. The Arizal himself maintains that one’s essential intention should be to the upper realms rather than the lower.

- 8. For R. Shalom Shar’abi, the Rashash, what is the purpose of kavvanot?

The Rashash looked down on attempts by other authors to speak about divine worship in an experiential register, as he believed that their attempts to do so effaced the Torah and did not reflect its true depth. The experiential is so lofty that it’s purposefully excluded from an esoteric work which plumbs the secrets of the universe and the nature of divinity. The Rashash intentionally wrote tersely. He states “I was brief regarding divine service in places where it would have been fit to expand a bit. This statement is true, for I made it brief purposefully (lechatchila).” (Nahar Shalom 34a).

Yet, he states that the work of kavvanot, focused on external cosmic worlds, gives way to an experience of connection and divine service because they are one and the same.

“All of our prayers are to the Ein Sof… according to the measured amount of clarification (birur) that one clarifies and raises up [of the sparks of divinity]… from partzuf to partzuf until the highest heights where they are fixed and return to be drawn down as mochin… then the ohr Ein Sof encased within, the spark and intermediary, is present and descends into every partzuf, from level to level to the end of all levels… then relative to us, we are justified in using names (kinuyim) [to address the Ein Sof directly]… and so too in the souls [narancha”i]” (34a).

The righteous individual is the vessel made physical; humanity is the partzuf which is trying to reconstitute itself, through a descent of the cosmic into the physical which causes it to “mitaveh” [congeal] (Etz Chaim 5:2). Our physical world is spirituality congealed.

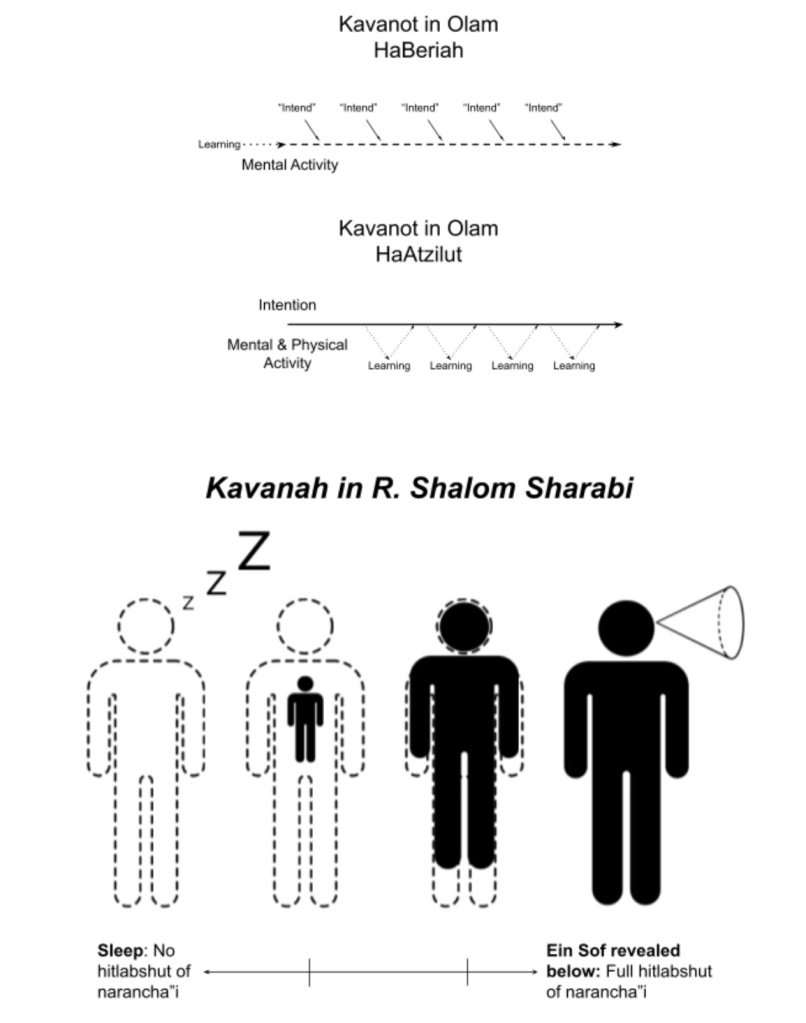

Based on Vital’s Sha’arei Kedusha, the Rashash hints further at the inner world cultivated through kavvanot. He calls the state of being where we cannot perceive the Ein Sof “slumber,” but through the devotional life of kavvanot, one can “awaken” the soul and perceive the Ein Sof (Nahar Shalom 39a). This state of wakefulness is one where the individual is attentive to the presence of Ein Sof in all things through their soul.

9. How is the Rashash different than Vital?

For Vital, the journey of the kavvanot of prayer is relatively linear: as one progresses from the beginning of the siddur to the peak of it at the Amidah, one is ascending in the worlds, and tachanun marks the inflection point where one begins to descend back towards our lived reality. Ein Sof is relevant in a theoretical sense to the entire project as we strive to connect to Ein Sof, but the essence becomes the medium of spiritual structures which we can tangibly access.

For the Rashash there is an immanent experience of Ein Sof which is possible because of prayer and that continues beyond it. Vital’s writings and the siddurim produced before the Rashash rarely, if ever, deal with Ein Sof directly.

The Rashash saw all of Vital’s writings as one fully unified corpus. Even concepts like the divine self-contraction (tzimtzum) with which creation began, largely beyond the scope of kavvanot in Vital’s conception, return to the foreground in the Rashash’s system.

Vital writes that the ultimate intent for creation was for the Ein Sof “to be called ‘compassionate’ and ‘gracious” (Etz Chaim 1:2). However, these terms which come up at the beginning of creation rarely recur in Vital’s writings on kavvanot or yichudim. Some commentators took these to be primarily of philosophical import alone for understanding the nature of reality and Being.

For the Rashash, even these seemingly theoretical statements are eminently practical understandings of kavvanot. Understanding the creation of the world as driven by the desire of the Ein Sof to acquire names is necessarily part of the contemplative practice of kavvanot, to experience Ein Sof within us, allowing us to recognize its attributes and to channel that into our prayer.

This difference influenced many of the innovations of the Rashash in laying out his siddur. Unlike previous versions of the Lurianic prayerbook, which formulated the kavvanot primarily as instructions, the Rashash’s siddur depicts each instruction with a series of divine names that symbolize the different layers of light affected throughout kavvanot. The deepest layer is “light (Orot)… the names of the lights are the souls (narancha”i) and are always the same… and never change at all… and the blessed Or Ein Sof is encased within them” (printed in Rav Yaakov Moshe Hillel’s Sfat Hayam Sefirat haOmer pgs. 276-277).

10. Are the Rashash’s kavvanot tikkun or hasagah?

For Vital, hasagah can be considered a consequence of tikkun. What we get from fixing the worlds allows us to continue to fix them even better.The system is cyclical. For the Rashash, the two could almost be said to be identical.

The Rashash believed that if we are truly meant to be considered as part of the cosmic realms, and if our experiences and perceptions fit into this schema, then tikkun and hasagah are basically identical, two perspectives on the same phenomenon. A person who practices this properly reveals the infinity of their soul within their body and wakefully encounters the Ein Sof within everything, especially themselves. The experience is immanent and relational and deeply unitive. The individual’s unity with the Ein Sof leads us to perceive that “all is made into one unity… in the secret of ‘I have placed Hashem before me always’” (Nahar Shalom 34a). Wakefulness is a contemplative state where our inner world is permeated with the experience of Ein Sof.

In the ultimate stage of tikkun, this experience becomes a metaphysical reality. The Rashash explains that Adam haRishon’s body originally extended across all the spiritual realms. The upper realms were literally his inner world, and they in turn were a container for Ein Sof. In true tikkun, we have a hasagah of what this was like.

11. For the 19th century R. Tzvi Hirsch of Ziditchov what is the purpose of kavvanot?

Just like in Vital’s writings and in the Rashash’s, for the Ziditchover, tikkun and hasagah are coterminous. Similar to the Rashash, the Ziditchover states that divine names are the key to connecting to the Ein Sof, as “our essential weapons [to purify the world] are the blessed names, to unify in them the vitality and the souls of every world… and the names are the soul of the sefirot, and the Ein Sof is the soul of the names” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 2b).

Unlike the Rashash, the Ziditchover writes openly about the personal transformation that one must undergo in order to practice kavvanot properly. Through learning Kabbalah, one can understand how to “imitate” them in our thought patterns and actions. We must utilize the Lurianic writings as maps for how to develop our spiritual self as we approach the Ein Sof. Ultimately, one ascends high enough to essentially transcend the normative practice of Lurianic kavvanot and enters into a state of mind where they can pray in true connection to the Ein Sof. The kavvanot are the gateway to this altered consciousness.

12. What is the role of the Eyn Sof for Zidichov?

A person directly relates to the immanence of the Ein Sof. The Ziditchover writes that the Ein Sof is revealed in the world through our actions: “drawing the Ein Sof into the divine names makes it become ‘that which permeates all worlds’ (memaleh kol almin) through the power of its essential holiness. Without this, the Ein Sof is removed from the world and its holiness… then the Ein Sof would not be called ‘creator of all worlds’” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 3b). But there is also a strong mental element as well: the Ein Sof is “the thought which descends into the world of emanation (Atzilut, the highest world)” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 1b). One’s thoughts change in the kavvanot of this world.

13, Explain intentional kavvanah vs reflective kavvanah according to the Ziditchover.

In the Ziditchover’s understanding, the light of the three lower worlds represents one’s thoughts, and the vessels represent one’s actions. One’s prayers are focused and intentional in the worlds of action, formation, or creation, which are called “the worlds of separation.” The divine light is not truly unified with the vessels that contain the light.

[The mind as it manifests when one is in the worlds of separation is not different from the mind that one exhibits in daily life: to focus on one thought, an individual has to continuously redirect their attention back to that thought as the mind naturally wanders, trying to keep its train of thought moving. In this state, the kavvanot are external to the mind. Hence, he writes that “the act of kavvanah shows a likeness to the world of creation” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 2a).

In contrast, the higher world of emanation (atzilut) is called “the world of unity.” It exhibits total unity between light and vessel, hence the intentions performed there are reflective of this. In the world of emanation, one must change thought itself to a reflective internal practice. He characterizes this form of thought unified with action as essentially reflexive: “for when a person eats, they need not think first how to chew with their lips, nor how to lift their legs to walk” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 1b).

There are two ways that this plays out. First, the desired result of prayer happens automatically, because one’s thought and the related action are completely unified. He writes that when one prays for healing in this state, “one does not direct thoughts to interpret ‘heal us” or certainly not to intend that there will be healing for them. It requires no intention because the healing is done on its own” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 2b). This elevated state of mind unlocks the mental potential to create whatever change we wish to see in the world.

Furthermore, the embodied nature of them as a practice blurs the lines between the body and soul. In this state, the Ziditchover states that in prayer “at times, they will raise their right hand, and we then know that the vitality desires wisdom [as wisdom, hokhmah, is associated with the right side], or he will raise their left hand, and we know that the soul and vitality desires to enrich itself.” (Pri Kodesh Hilulim 3b). In this elevated state of kavvanah associated with the world of emanation, new and timely kavvanot will also emerge as one observes their own body’s movements and interprets the meanings. Connecting to the immanent Ein Sof opens up a wellspring of creativity to create these new kavvanot.

14. How do the Rashash and the Ziditchover differ in their understanding of how kavvanot work mentally?

For the Ziditchover, when one practices kavvanot in the worlds of separation, one must constantly direct their mental activity to particular intentions. These are external, needing to constantly be reintroduced throughout the practice. As the mind wanders naturally, one must continuously reintroduce the thought of “intend.” Once one arrives to the level where thought and action are unified, one’s mental and physical activity is unified and needs no conscious redirection: all of one’s actions are the state of kavvanah. However, one can observe one’s physical activities and “learn” from consciously what is subconsciously expressed by the body’s movement in the act of intention.

As for the Rashash, the more one practices the kavvanot, the more one’s soul (the inner seat of the Ein Sof) expands within and controls the body. Thus, one’s internal and external perceptions are transformed as one sees the Ein Sof within and without. Without this understanding, one is called “asleep,” and one who fully achieves it is “awake.” The perception of a person who experiences this wakefulness not only sees the Ein Sof externally, but also internally as well.

When comparing the Ziditchover’s and Rashash’s approaches to kavvanot, we find many important similarities. These include quoting shared source material, relevant historical leanings or beliefs related to kavvanot, and more. At the same time, we see important differences in the mechanics of the kavvanot and their results. It would be accurate to characterize the similarities as more theoretical beliefs about kavvanot and the differences as pertaining to practical elements. The first chart shows the similarities and the second chart shows the differences.

15. What is the subjective experience of kavvanot?

I can only really say at this point how it feels to me. The focus that kavvanot necessitate becomes an opportunity to slow down and savor the experience of prayer. Doing them for long enough strengthens my concentration and makes me more aware also of my body and my surroundings. Time feels slowed during this practice. I find that doing them draws my attention to a pleasant feeling in my body, particularly in my head. Over time, I have ascribed personal understandings and feelings to different kavvanot—there are parts that I connect with more, during which I feel more deeply.

Even though kavvanot are very mentally active and I am trying to follow the instructions of the siddur, my inner monologue is not only the words on the page but associations or prayers that I connect to these parts. It is an energizing and activating practice. They can awaken a feeling of intensity and passion, of movement even. I think of this as hitlahavut. Often, I will take a deep breath and pause for a moment within the practice and find myself awash in an “oceanic feeling,” one of calm and connection. This is what I think of as deveikut.